Would you pick up this Crier? Students question the meaning of school rules

When you see paper scattered on the ground, the right thing to do is pick it up. Would you?

November 12, 2021

You’re exiting study hall when, suddenly, crumpled brown paper towels hurl past you, heading toward the trash can and missing horribly. The room is now empty, and you’re surrounded by paper towels littered across the floor. Would you stop to pick them up, or plug in your AirPods and walk to your next period?

When no one’s watching, it becomes far less likely for someone to pick up the scattered pages of newspapers that can litter the Commons hallway after lunch, or resist the urge to peek at their phone during study hall. Whether school policy or general social expectations—such as picking up the trash around you—the fluidity of some rules cause their purpose to lose its original meaning for students, serving more as guidelines to adopt when convenient.

“At the end of the day, a lot of kids don’t really have the patience to truly care, at least in our generation,” Jaylin Turner, senior, said. “So, it’s more so you’re following the rules to get by, rather than actually caring about what it is.”

This sense of lackluster adherence becomes evident in some of the more violated policies at school. Take phones, for example—in a Crier survey of 347 students, every two out of five agreed that they never or almost never adhere to the no-phone rule at school.

“(Students are probably learning how to) play the system,” Mark Robinson, senior, said. “For me, using my phone in the hallway is not ruining my future or anything. It’s not that big of a deal. Certain things are a big deal but not that.”

As of this year, the MHS phone policy has been changed so students whose phones are taken away cannot lose them for an entire day. Despite these seemingly minor infractions of school code, for many students, especially those who transferred from districts outside of Munster, MHS still clearly ranks better in terms of behavior. For Madi Green, senior, the sudden shift from attending elementary school in Hammond for six years to Munster in seventh grade, required immense mental and social adjustment.

“I’ve noticed that Munster kids are a lot more tame,” Madi said. “A big thing that I noticed on my first day of school in seventh grade at St. Thomas Moore (was when) the teacher left the classroom for a minute. Back at (St. John) Bosco whenever a teacher would leave the classroom chaos would break out, but here everyone stayed quiet. It was a big cultural shock, really.”

Some attribute this sense of better behavior to the more stringent enforcement of certain rules. Kam’Ron Hawkins, senior, did not just experience culture shock when moving to MHS, but struggled with the technicalities of school policies, such as tardies. Riding the bus, he had little control over being late to his first hour on particular days, but was reluctant to speak out when he suffered for it. Many students, including Kam’Ron, learn that conforming to school rules is not just a matter of mental readjustment, but academic and social success.

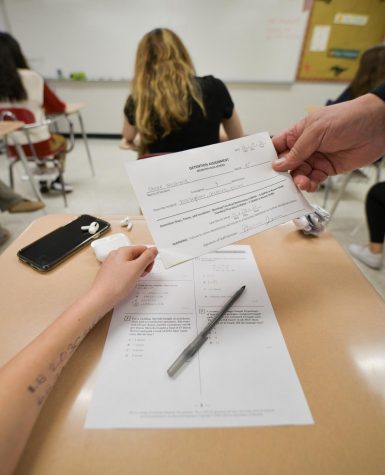

“It was different because most high schools are not really strict on most of the rules here,” Kam’Ron said. “So when I got here, I was trying to settle down and get comfortable with the phone policy and…tardies. It was irritating because (I got) back to back detentions and (an) ISS (In-School Suspension). They really take you from learning because when you are suspended, your grades just drop immediately.”

For Jaylin, the contrast between surface-level, obedient adherence to order and the underlying, unmotivated attitude of students is reflective of the more sinister side of school rules. According to Jaylin, students are not learning to follow them for the sake of it, but rather when and where not to act responsibly.

“I’d say school rules teach you who to use certain rules with,” she said. “This isn’t necessarily good, but we have (certain instances) of, ‘Oh, you have good grades, I’m going to let you slide on this,’ but it depends on the teacher as well.”

Inequality in treatment varies across the board with students. According to Jaylin, Madi and Kam’Ron, students of lower academic or social standing disproportionately face harsher punishment for a school rule violation. This disparity may also contribute to student apathy not only in regards to certain school policies, but grades and extracurricular activities.

“There’s strict rules for what your academic standing must be to participate in extracurriculars,” Akansha Chauhan, senior, said. “This is harmful for the majority of kids. For me, it was beneficial because I like STEM, and that environment was suitable for me. But (for) a lot of kids who aren’t interested in that, it’s not fair to push those priorities on them in the same way.”

How do you feel about certain school policies?

Whether intensely involved in school or not, the disconnect some students feel between a rule’s purpose and its effect can be traced back to the high standards of MHS. For many students, pressure to succeed at any cost is a typical sentiment. Though the honors system may be a source of academic motivation, it can create feelings of competition and a sense of hierarchy. This feeling is especially magnified for those raised in the school system from a young age, according to Maya Queroz, senior, who began to notice this phenomenon in her third grade honors English class.

“The first thing I understood was that these people are sometimes my peers and sometimes competitors,” Maya said. “I feel like the message the school puts out is overall positive, but it definitely has competitive undertones that the students feel, especially when they were raised in the school system.”

Students like Madi argue that this competitive atmosphere is palpable in the way rules feel optional to students on both sides of the coin: students of high standing, she says—whether that be through participation in clubs, exceptional grades or close relations with teachers—are at times awarded for their achievement with more lenient punishment, whereas students of lower standing in this hierarchy see no reason to try.

“I know that I can’t compete with most of these people,” Madi said. “I just keep to myself, because I can’t really relate to them. I don’t feel a need to compete because I know I won’t be able to match up to them no matter how hard I try. I didn’t have the full Munster background experience.”

Despite this, some argue that imperfection in the implementation of rules is inevitable. To address this issue, real focus should be redirected to a rule’s purpose: preparing students for the real world.

“I think rules are a part of society,” Mr. Mike Wells, principal, said. “Rules are something that you’re going to have to follow the rest of your life no matter what career you choose. You can’t be disrespectful to your boss or you’re going to be fired. There’s a lot of learning lessons that are going on, besides what you’re learning in the classroom.”

Many students agree that clubs and classes that engage interest on topics of civic responsibility, and even identity, can help encourage students to reframe their perspective on certain school policies. Organizations that allow them to directly communicate with administrators, like Inclusion Diversity Equity Awareness (formerly referred to as Supporting Minority Students) also empower students to take a more active role in school policy.

“Especially since there are a lot of administrators that are in the IDEA group, it helps when there are students to talk to them,” Tyra Wheaton, junior, said. “Certain things people genuinely don’t know until someone tells them. One of the main things that we talked about was representation. Everything starts with representation and when we don’t have any, it’s really hard to even try to make a change.”