‘Teaching is more of an art than science’: In attempt to shift Munster more student-oriented, teachers reflect on how that process looks

April 20, 2023

GETTING THE BALL ROLLING Presenting to a crowd of teachers, Mrs. Tammy Daugherty, instructional coach, speaks to teachers about the performance of students and time management.

What students actually thrive at Munster High School?

The student performance data has stayed pretty consistent—to almost every student’s knowledge, MHS students rank in one of the highest percentiles in Indiana.

But in that same vein, the gaps in achievement—economically disadvantaged students, students with disabilities, individual race—have remained stagnant.

So, what is MHS—what are teachers—doing to improve this data?

“Not every kid is hitting the benchmarks to be college and career ready,” Mrs. Tammy Daugherty, instructional coach, said. “If what we were doing for all these years is getting the same results over and over again, that’s insanity. What is it that helps bring and close those gaps between vulnerable populations, sub populations?”

Why aren’t teachers in class—why can’t students see teachers in the morning? Or, what goes on when all the teachers in one department leave to “curriculum map”? These are the questions that I asked all last semester.

Eight weeks ago, I started attending meetings to find out.

I went to five Professional Learning Community or PLC meetings, I saw one curriculum mapping session and I attended seven Professional Development or PD meetings.

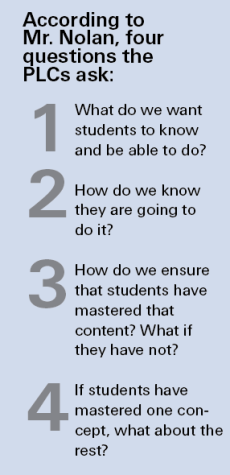

The idea of ensuring that all students have the right to learn is just one piece behind the Professional Learning Community and Professional Development process. The general approach, according to Mr. Morgan Nolan, principal, is defining what students should know and how they should measure that.

“How do we ensure that it’s not just by selection or by opportunity base that students have a chance to learn?” Mr. Nolan said. “A lot of teachers feel that learning is a choice. I have a fundamental disagreement with that—we have an obligation to ensure students are learning at high levels. I really do think that we should have this mentality of we’re gonna make sure everybody’s learning at high levels. It’s not a choice.”

What do I have to do with it? Keeping this philosophy in mind, I moved to exactly what teachers actually do at these meetings.

Thursday morning meetings: Seeing teachers’ PD

The general premise of these meetings this semester is how to allow students to take charge of their education, rather than simply speaking at them.

Teacher discussion was one factor at all of these meetings. Some teachers enjoy breaking down standards, especially when it comes to talking to other teachers and realizing their own standards are too broad.

There was, I noticed, a clash when it came to creating ‘I can’ statements. In some ways, as I listened in, they allowed students to know exactly what they were learning. On the other hand, is simply putting them up on the board enough?

In addition, some teachers noted, how do standards actually co-exist in the classroom—if each teacher for a certain subject has the same standards, how much does that impact their autonomy? At one meeting, during the breakdown of standards, a few teachers noted that they felt a lack of trust when it came to teaching in their own classroom.

“The Thursday meetings are rushed,” Ms. Valerie Pflum, math teacher, said. “We keep going, without having stopped and said, ‘Okay, let’s try this for two weeks.’ I do like the PLC process, but it makes me sad some people were not doing it already. It’s not that big of a deal for me to sit in a PLC, but I know 40 minutes once a week is not enough. If you want people’s private ways of teaching to change, you have to provide the PD on it. I hate to say it, but unless you show the Social Studies Department how to do it in a social studies room, they’re not necessarily going to make that connection.”

Mr. Nolan held PD sessions on student ownership of learning during the first semester. When it comes to the teacher meetings, for the most part, students only know that teachers are absent—the meetings themselves are foreign. But Mr. Kevin Clyne, English teacher, believes that while PLCs address the concept of student ownership, it has yet to be fulfilled by the meetings themselves. When staff map out the curriculum, breaking down state standards, they use it as a guidepost for learning.

“The thing is when we get in the room to map, we don’t talk about you as a student,” Mr. Clyne said. “We have never really said, ‘Why are students taking this class? Why not? Because it’s required for graduation? Because I’m often like, ‘How can this be ownership?’ We’ve never talked to a student.”

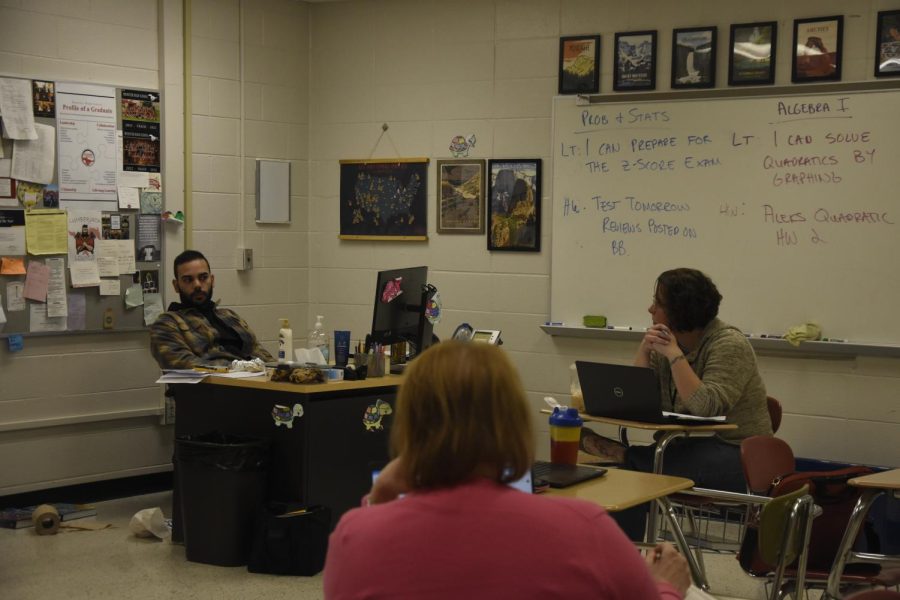

Daily Meetings: Being Part of a PLC

My next question stemmed from the daily meetings themselves, especially with students wishing for the appearance of contact time, or more designated time with their teachers. What else is it that teachers are doing, then, to benefit students in the classroom? Why should students care?

Each morning meeting I went to varied. Some courses spent time directly looking at tests and how they measure student knowledge, whereas other PLCs spent time with discussion outside the curriculum. However, Mr. Matthew Kalwasinski finds that the PLCs have only been positive in terms of collaboration—though he is the only AP Psychology teacher, he still uses his PLCs as an opportunity to gain more knowledge about writing in AP-style FRQs.

“The PLC process has been an adjustment but only in a good way—it forces people to get together,” Mr. Kalwasinski said. “At the beginning, there were a lot of unknowns on what the point was—what was our goal? But there’s nothing wrong with saying, every day, or once a week, you’re getting together with other people who teach your subject and talk about ‘What’s working in your class? What’s not working in your class?’ I laugh at myself for what I used to do years ago when teaching.”

Reaching a point of no consensus is inevitable, Mr. Clyne reflects—but is that a part of the process? In some ways, it becomes an issue with several teachers with unrelated subjects collaborating all at once. The idea of creating a culture of collaboration is something several teachers value—however, it has brought up questions about teacher autonomy. Part of the purpose behind a culture of collaboration includes Mr. Nolan’s efforts to get teachers to come together with new ideas, rather than teaching to themselves.

“Teaching is more of an art than it is a science,” Mr. Nolan said. “Most people come into education, close their door, and teach by themselves. And I’m trying to tear down that barrier to show that there’s a professional culture here, and that if your kids are struggling in your classroom, it’s not your fault, but it is your problem to solve. But you don’t have to solve it on your own.”

The subject of teaching by oneself comes to a head at these meetings when it comes to whether or not teachers create identical learning targets—a question that has not been definitively answered yet. But the purpose of creating these learning targets—some of the ‘I can’ statements we’ve seen on the whiteboards in the last few weeks—is to do what is best for students.

“I’m actually supportive of the idea that learning should be a little sloppy,” Mr. Michael Gordon, social studies teacher, said. “You don’t go directly from A to B. The goal of a PLC is to encourage discourse, not to force standardization. But if you and I are teaching the same class, and we’re talking about it, it’s almost inevitable that I’m going to copy some of the things you’re doing. Ideally, we’re going to copy the ones that work best. Will that lead to some degree of standardization? Probably. But the goal is not standardization. The goal is improvement in instruction, reinvigoration and how we take on our class.”

How does that relate to students? The process is slow—but, in theory, it is designed to prevent our school district from staying stagnant.

“In that old traditional mode of teaching, I’ve seen teachers plan out 180 days in advance,” Mrs. Daugherty said. “They know exactly what they’re doing when they’re doing it—some worksheets have been copied so many times you can’t even read them. This flies in the face of that because you don’t know how your students are going to react to your instruction. How students respond dictates what happens for you in the classroom.”

One of the barriers in creating this shift is the attitude—the structure is there, but it is left up to the individual teachers. At some individual PLC meetings, some teachers speculated how long this process would last. On the other hand, is fostering a culture of collaboration something Munster should have been pushing towards in the first place?

“Teaching is more art than science, and teaching is an extension of the personality,” Mr. Gordon said. “But if you have three different teachers teaching the same class, the classes are fundamentally different. We pretend that they’re not. I’d be lying if I didn’t say that my favorite part about teaching is closing the door and making this room my world. My happiness and sadness in the profession is so related to the world that I create. There’s an inherent uncomfortableness in opening up that door and sharing that autonomy with others. But that discomfort is not a bad thing. Having a culture of collaboration is an incredible value.”