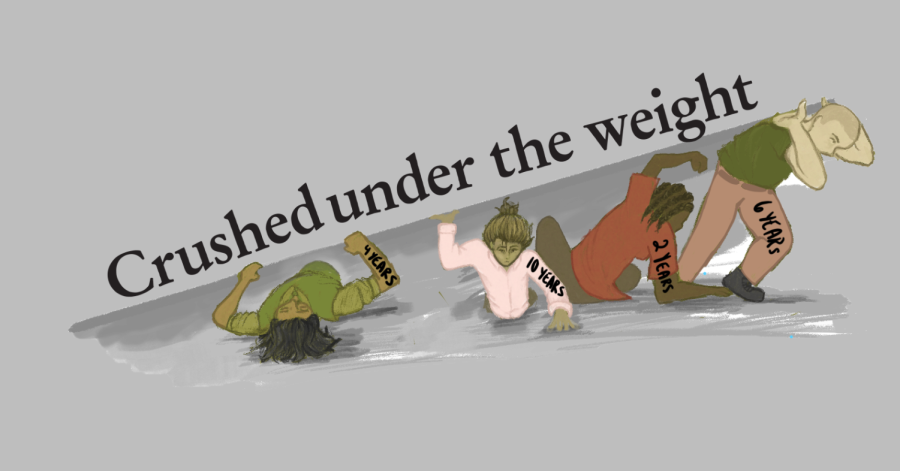

UNDER PRESSURE Representative of the pressure teachers are put under, the National Teacher Shortage has consequences on teachers of all ages.

With talks of a National Teacher Shortage, teachers and students discuss its implications at MHS

When you first click on the webpage for Elevate K-12, the program MHS is using to provide an online teacher for anatomy courses, the first line that appears is: “Live teaching can solve your teaching shortage problem, as shown in recent news coverage.”

For the past two months, Mrs. Brianne Sabaitis’s anatomy class has had an online teacher in place of her while she is on maternity leave. On a national scale, the phrase “National Teacher Shortage” is everywhere—according to the National Education Association, schools are facing a shortage of 300,000 teachers and staff.

Though teachers’ opinions vary as to what the future of teaching looks like, Mr. Thomas Barnes, English teacher, considers it a cycle that will eventually result in a culture shift where teaching will become more popular again. But his biggest fear is education turned automated.

“There are a lot of things that you learn from a teacher without requiring you to give students piles of work,” Mr. Barnes said. “Teaching is a bit of an art. You either make connections with kids or you don’t. Students appreciate that a whole lot.”

Regarding his fear of teaching becoming automated, he finds that, at this point, he could simply monitor 30 or 40 kids—but that is not the purpose of teaching. To Mr. Barnes, the pandemic exacerbated the idea of ‘Why do we even need teachers in the classroom?’ A National Education Association survey found that 55% of educators are thinking about resigning earlier than they had planned—in recent years, some teachers find that there has been a culture shift in terms of being targeted for political indoctrination.

“There’s been a lot of hate on teachers and misunderstanding about what we do as a job,” Mrs. Kelly Barnes, English teacher, said. “I think a lot of it started politically, with Critical Race Theory. But it does seem like in a lot of districts—not necessarily ours, we are fortunate—parents are very scrutinizing of teachers. That puts so much more unneeded stress on the teachers who are just trying to help kids. Some people think we have a hidden agenda for what we’re trying to indoctrinate kids about. That has put a sour taste in people’s mouths about the education system, and I think that makes people not want to stay in education.”

As teaching progresses, generational differences are believed to factor into the shortage—but not on its own. Ms. Robyn Brown, a new math teacher at MHS, finds that entering the profession in the time of a shortage means more opportunities. However, she had this passion since she was young, and acknowledges a cultural shift. To draw other younger teachers in, Ms. Brown wants to make education a positive experience for her students.

“Since I was young, I always knew I wanted to be a teacher,” Ms. Brown said. “I was not deterred by the situation. The shortage is sad because I think there are a lot of people who have that passion for helping other people learn. But there are outside factors—if they are at a school where the administration is not supportive, or there is a cultural shift and maybe teachers are being less respected.”

According to the Collective Bargaining Agreement for 2021-2023, the starting salary at Munster is $51,000. In a recent decision from the state, staff is receiving up to $790 in stipends depending on rating, money already granted by the state. Toppled by issues with salary and increasing pressure, teachers are struggling with the workload placed upon them. Mrs. Barnes worries the issue will make its way into the dual credit system. The Higher Learning Commission wants dual credit teachers to have a masters in English—something only English teachers Mrs. Barnes, Mr. Benjamin Boruff, and Mr. Steven Stepnoski have. Teachers with a master’s degree receive a $2,000 year bonus.

“The shortage has caused a rift in certain situations,” Mr. Morgan Nolan, principal, said. “We’ve been forced to hire teachers with a lot of experience, and some of them have bigger salaries. They’re coming into a school district where somebody has been here for 13 or 14 years, and then someone hired in the first year here is making more than the person who’s been here. That’s new in education. Part of it is a teacher shortage issue. A lot of times those are people coming from other school districts looking to get into Munster, and that hurts other school districts.”

According to Education Week, shortages may be more prevalent in specific areas of the country. In the past, Mr. Nolan says, hundreds of teachers would apply for positions. Now, those numbers have dwindled down to around two or three. When it comes to the reasoning behind the national teacher shortage, Mrs. Kathleen LaPorte, social studies teacher, believes it comes from a lack of interest in teaching for several reasons.

“Teacher shortage is an interesting semantic because there is not a shortage,” Mrs. LaPorte said. “There are teachers everywhere—they are just leaving the profession. New teachers are overwhelmed with what is now on their plate.”

16 years ago, Mrs. LaPorte entered the teaching profession. The community then was much different—there were ideal benefits, many teachers stayed after school coaching sports, and teachers could see what the future looked like in terms of salary and teaching.

“I am really glad that I’m in the second half of my career,” Mrs. LaPorte said. “I hope it doesn’t change enough so that my 5-year-old can graduate from MHS or any public school for that matter. If that doesn’t sum up my fear for all of that, I don’t know what does.”

Many teachers found the shortage to be predictable, but for different reasons. Mr. Steve Lopez, social studies teacher, has seen the signs for many years. For Munster in particular, there was a change after the financial crisis—despite the fact that there were benefits to the Munster community, teachers still had to make a living.

“The biggest change, in the years that I’ve been here, is the lack of ability to be autonomous,” Mr. Lopez said. “I got into teaching because I wanted to be able to control my own destiny—my schedule and life. Teachers can do that to a degree, but they’re also told by a line of directors: ‘We think you’re doing this wrong.’ It could be something drawing teachers away. The political perspective has been overblown. It’s more on the administrative level. They’re not hitting you on the content, the way that the state might suggest, but they are hitting you on methodology.”