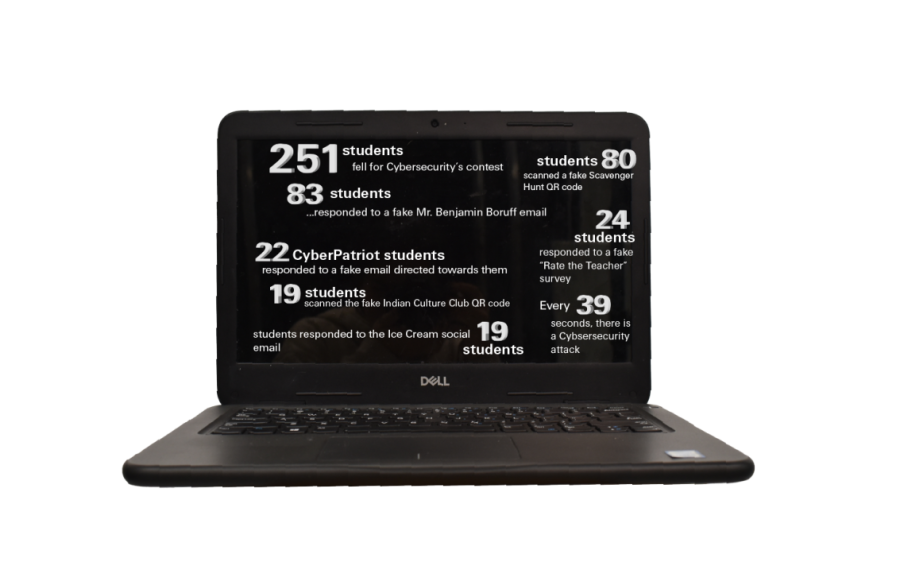

GRAY HAT HACKING Shown above are the results from the project conducted by Mr. Ryan Popa, cybersecurity teacher’s, sixth hour class.

From the inside: For Cybersecurity Awareness Month in October, Cybersecurity students “hacked” the school

Putting a spin on his teaching, Mr. Ryan Popa, cybersecurity teacher, presented a new project for his students: send out fake emails all throughout the school, and see how many responses they can get. The goal was to prove that they could have been more malicious in taking personal information.

A few weeks later, an email was sent out impersonating Mrs. Leigh Ann Westland, English teacher, trying to steal student bank account information. As Mr. Popa went to create an email letting the school know his project was fake, he received information stating that the hacking attempt was real.

“The big thing about cybersecurity is ethics,” Mr. Popa said. “If somebody heard about our contests and was like, ‘that’s a good idea’ and took it a step further, trying to get people to bank information. That’s what’s scary about the class, it’s not rocket science—everybody’s got a computer.”

Initially, only Mr. Morgan Nolan, principal, knew about the project. The students were able to bypass the school’s security system as their attempts contained no real malware. Cybersecurity’s project bordered on gray hat hacking—perhaps they broke some ethical concerns, as no one else knew about the project, but there was no harmful intent. In this case, the results did teach about students’ ability to pay attention—students fell for the bait “hook, line and sinker.” The email that gathered the most responses impersonated Mr. Benjamin Boruff, English teacher, with 83 responses; it was sent by the contest’s winners, seniors Victoria James and Neel Patel, Molly Platis, junior, and Stephen Glombicki, sophomore.

“Just by taking a few key components of how teachers talk,” Victoria said. “With Mr. Boruff, I was able to do this from one email from him on what we were trying to spoof and an email list. I appealed to empathy, and said it was for SATs and application week.”

Victoria’s strategy towards garnering responses reflects strategies real hackers use to gather information. Moreover, the results were a red flag for Cybersecurity students—how much do other students actually know about Cybersecurity? A large component, according to Victoria, comes from just looking twice—even some CyberPatriot students were fooled into responding.

“The more they know about you,” Mr. Popa said. “The easier it is to hack you. Most people think hacks are done in a dark room, typing on a keyboard, but really most hacks start by being a social engineer—taking advantage of human weakness with human psychology.”