Editorial: Education matters

February 24, 2022

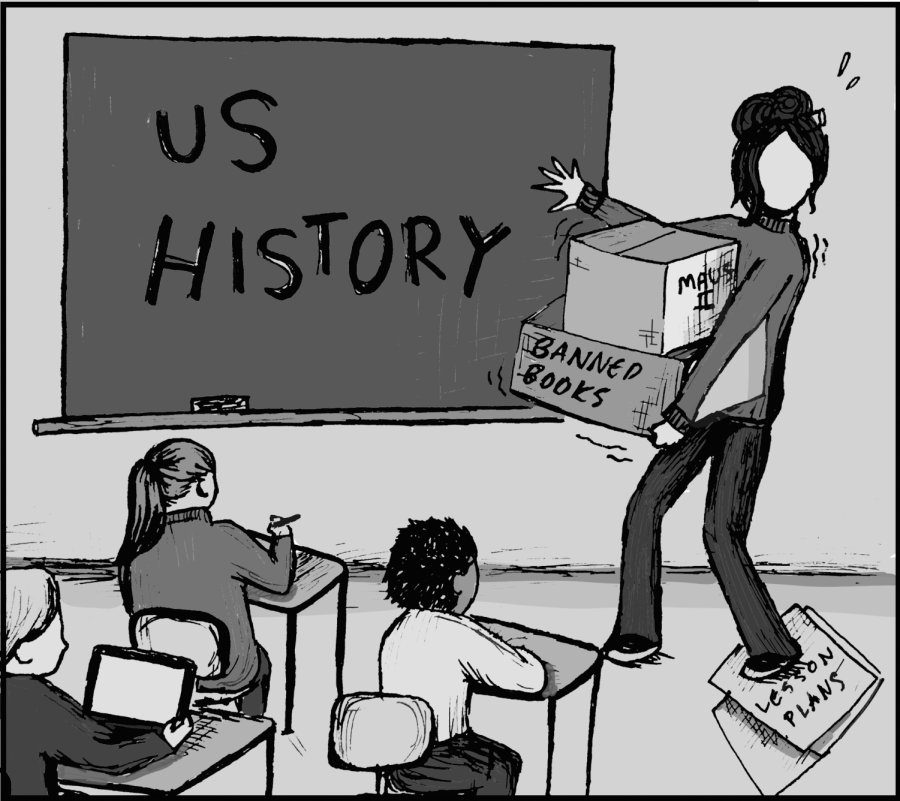

In an adapted version of his 2020 book “School House Burning: Public Education and the Assault on American Democracy,” law professor at South Carolina Law School Derek Black argues that public school education is essential to uphold and reinforce American democracy. Public education, he says, is the crux of democracy, and much of public education’s its current endangerment, he says, is caused by the political polarization we face today.

HB 1134 is a prime example of political polarization manifested into the public education debates. Not only would the bill force teachers to remain neutral when teaching topics covering race, history and politics, but it punishes teachers who may “violate” this mandate of neutrality. It also gives parents the option to opt out of particular lessons, further encouraging stagnancy and short-sighted perspectives, and pitting parents against teachers.

It is important to note that many educators are calling out this bill for solving a problem that never existed: teachers’ goals are not to instill personal ideology into their students, but to provide them the tools to think critically. Even more, parents already have the ability to review curriculum. Educators state-wide are planning multiple gatherings at the state house in Indianapolis in opposition to the bill, and there are fears of a mass exit of teachers from the classroom if the bill is passed.

Neutralizing important conversations on history in schools is to insinuate that race, gender and political affiliation is considered neutral in America today., and that the country’s legacy of racism and sexism does not still affect us. Take the Civil Rights Movement, for example. Though proponents for the “education matters” bill express fear that the way we teach historical events, such as life for Black America under Jim Crow, can harm students, it can easily be argued that Americans do not learn enough. Few people know that Ruby Bridges—a woman who was the first Black child to desegregate William Frantz Elementary school in Louisiana—is only 67 years old. Education on historical events like Black history are often limited to shallow lessons that may include hope for America’s future of pluralism, and are usually only revisited during Black History Month. In a Washington Post analysis piece two weeks ago, national correspondent Phillip Bump points out that arguments against teaching critical race theory—a 40-year old concept that studies racism as a systematic institution—often fail to recognize racial discrimination as a current American issue. Before blindly shutting down race-based conversations in fear of divisiveness, we should take the time to consider implementing educational systems more beneficial to students of color.

Supporters of HB 1134 will say that it protects children from social-emotional trauma, but here’s the truth of the matter—racism has a far more detrimental effect on kids. Just look at the American Academy of Pediatrics’ policy statement on racism and its impact on children: racism is a proven social determinant of health. Even more, HB 1134 prevents schools from providing “mental, social-emotional or psychological services” to students “without a written request for consent”—a move paradoxical to its goal to protect students’ emotional wellbeing.

Education should be uncomfortable. The only way to critically examine our world and prevent travesties, such as the Holocaust or Jim Crow, from happening again is by educating future generations on our dark past, and acknowledging humanity’s tolerance for cruelty. HB 1134 does not protect students but, rather, stunts their growth as well-rounded citizens, and protects America from recognizing the consequences of its actions.

![SNAP HAPPY Recording on a GoPro for social media, senior Sam Mellon has recently started a weekly sports podcast. “[Senior] Brendan Feeney and I have been talking about doing a sports podcast forever. We love talking about sports and we just grabbed [senior] Will Hanas and went along with it,” Mellon said.](https://mhsnews.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/sam-892x1200.png)