Hallway hullaballoo: the increase of hallway traffic

Students and staff discuss hallway traffic and how to fix it

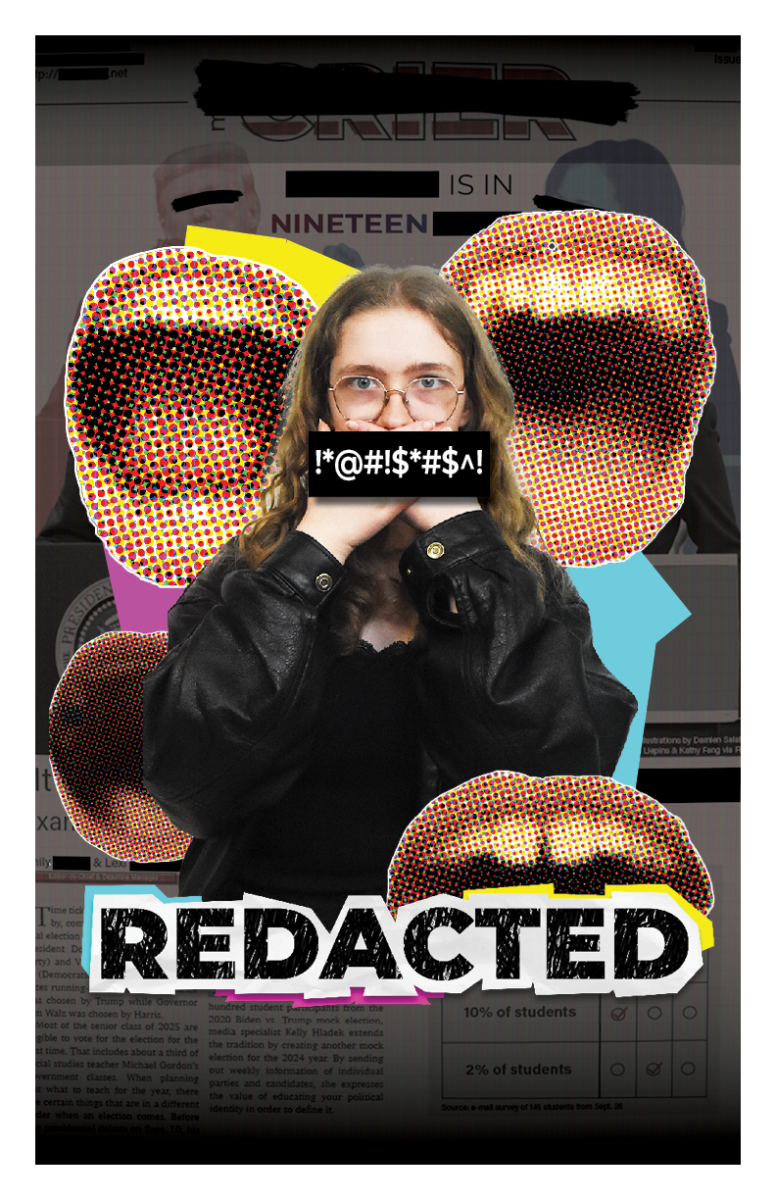

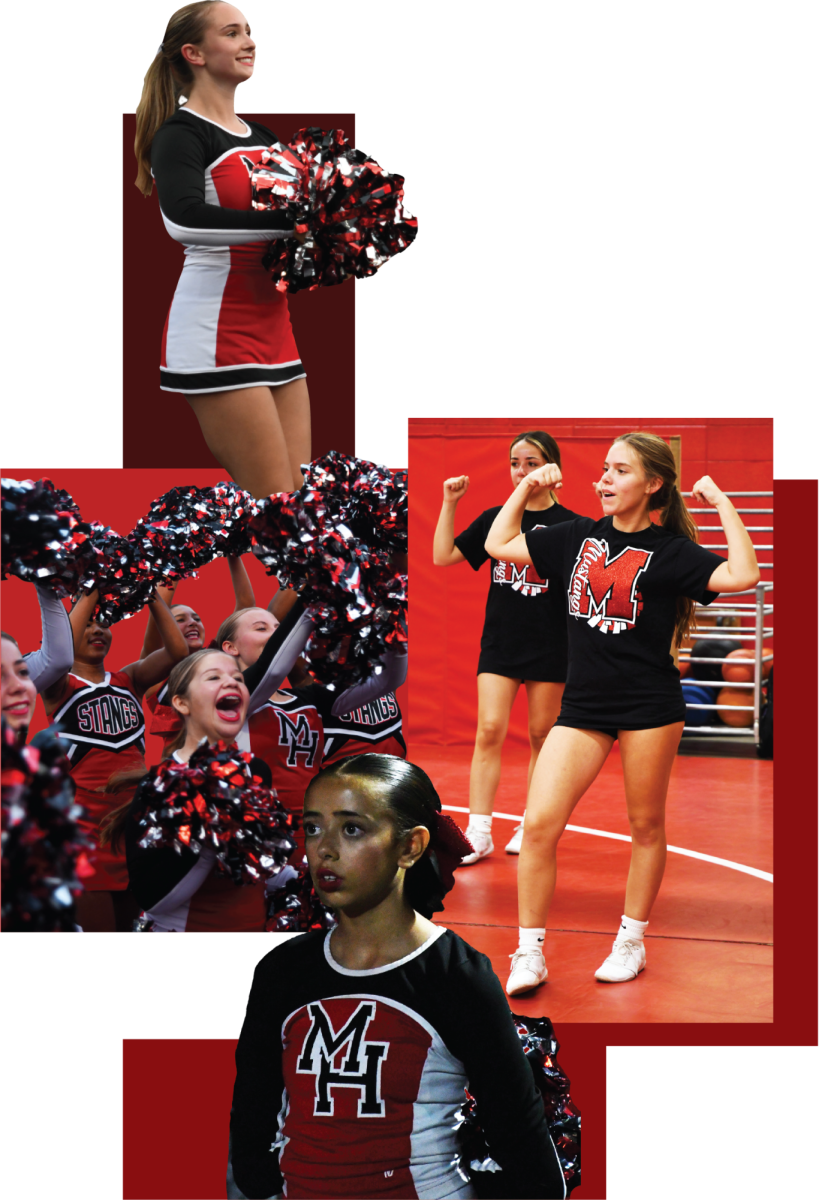

A HERO’S JOUNREY Matthew Barnard, Alexis Burleson and Ava Cheffer, juniors, walk through the hallways on the way from 4th to 5th hour. This particular area by the mural on the north side of the school is often one of the most congested hallways.

December 15, 2021

The bell rings, launching you into the long trek from Algebra to US History. You power walk around clumps of chatting students and fight the torrent of underclassmen pouring down the wrong side of the hallway. After being jostled and shoved, you finally emerge into North—only to be waylaid behind a group of slow walkers, four-wide.

“Chaotic is the best word to describe it,” Madeline McFeely, senior, said. “One thing I’ve noticed especially is people not walking on the right side of the hallway and going against the flow of traffic. The passing periods are a mess.”

According to Madeline and many others, the peaceful hallways from eLearning last year have thrown the return of the chaotic status-quo into sharp relief. It’s not only seniors, the one remaining class to experience a full year of high school pre-covid, who have had to readjust to passing period pandemonium.

According to Madeline and many others, the peaceful hallways from eLearning last year have thrown the return of the chaotic status-quo into sharp relief. It’s not only seniors, the one remaining class to experience a full year of high school pre-covid, who have had to readjust to passing period pandemonium.

“I think it’s gotten a lot worse this year than it was last year, the hallways are definitely a lot crazier. Like, I seem to bump into a person at least every day,” Eden Cook, sophomore, said.

Adding to the confusion are freshmen and eLearners who are new to the building and its rules. With the ever-changing adjustments expected of the student body after covid, learning basic hallway etiquette (like walking on the right side of the hallway or following traffic flow) has taken something of a backseat, Madeline says.

“This is the first time our freshmen and sophomores are learning what those norms are,” Mrs. Kristin LaFlech, business teacher, said. “I think even juniors and seniors need to be refreshed on etiquette and how we act in the hallway.”

Mrs. LaFlech is forced to be extra aware of hallway hazards due to her recent knee replacement surgery. As one of the many members of MHS who has difficulty navigating during passing periods, she voiced concern for anyone with handicaps or sensory issues.

“The thought of walking in the hallways gives me a sort of anxiety,” Mrs. LaFlech said. “I have to wait until all the students are clear. If one of them nicks my leg, I’m going down. […] I could not imagine if, say, I had special needs—being out in the hallway all the time, it would just be a sensory overload.”

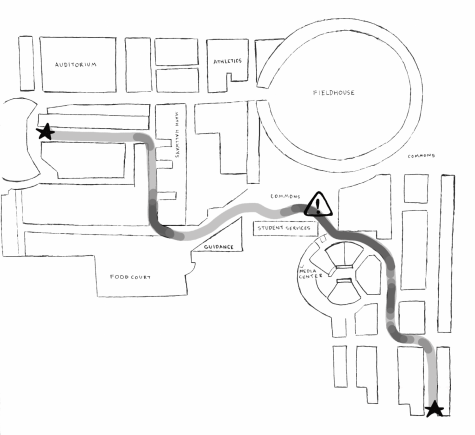

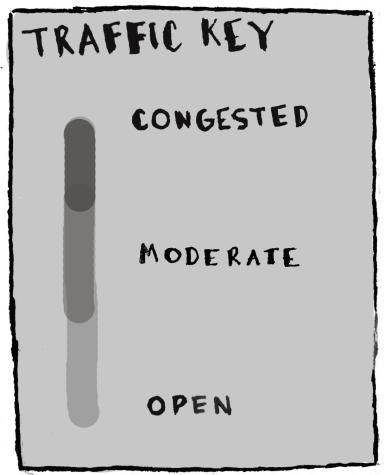

Some areas are worse than others—especially on the North side of the school, intersections, and around the lunchroom. “Funnel” areas that bottleneck traffic, like the entrance to North, are particularly crowded. But according to Mrs. LaFlech, this issue runs deeper than logistics and crowd flow—it’s a social problem at its core, she says. The disorder in the hallways is a uniquely high-school experience, and many students share her observations.

“I feel like once you get out in a public or office setting, people have had enough life experience to know proper etiquette, and just to know when to stay on the right side—you walk at a normal pace. But in the high school hallways, people still haven’t had that life experience,” Madeline said.

MHS has an enrollment of 1,616. Packing such a large number of 14 to 18 year olds into a small space inevitably creates a culture of chaos that has made many students feel unsafe–over a quarter, according to a recent Crier survey.

“It’s a learned behavior, you know?” Mrs. LaFlech said. “Nobody pays attention. It’s just a lack of fundamental understanding of social norms.”

At the same time, passing periods have become an essential part of how Munster students develop this much-needed social awareness. With eLearning and cancellations last year, students jump at the chance, however small, to reconnect with peers again outside a classroom environment.

“The social piece is so important to [students’] development,” Mrs. LaFlech said. “That’s where [they] learn social norms. I think that that’s so vital. [… students] didn’t have that for a year and a half, it’s pretty brutal.”

According to MHS students and staff like Mr. Thompson, science teacher, covid has made it more obvious than ever that hallway traffic needs improvement, but equally clear that students need social time—so how can students be allowed to reconnect without crowding one another?

“I would say wider hallways,” Mr. Thompson said. “But I don’t think that’s an option. Or maybe, having four lunch hours instead of three. Block scheduling might make it less frequent. But those are pretty major changes, I don’t think any of it would be worth it.”

Other ideas for curbing the chaos range from simple to innovative: changing routes, shorter passing periods, allowing seniors to cut outside, and many more. Amidst the creative stew of possibilities, one overarching solution emerges–each student making an effort to be more aware of their surroundings and consider others.

“People don’t respect each other’s space, sometimes. Or they don’t slow down to let other people cross. Or other times people will group together in big clumps, and you can’t get through. It’s just because you’re not noticing, and only being focused on the people around you,” Eden said. “I think you should just pay attention to what’s happening around you while you’re having a conversation. Just make sure you aren’t blocking anyone’s path.”

Most of the problems that cause congestion in the hallways—people not following the flow of traffic, blocking others, pushing, congregating in large groups, walking slowly, etc—could be resolved with a simple thought: Am I being considerate to the other people around me?

“Want to talk? Walk and talk. If you’re with a group, try not to spread out across a whole hallway. Don’t block other people. Don’t just randomly stop, and if you do want to stop and talk, pull back to an area that’s not super crowded,” Madeline said. “Just be polite.”

![SNAP HAPPY Recording on a GoPro for social media, senior Sam Mellon has recently started a weekly sports podcast. “[Senior] Brendan Feeney and I have been talking about doing a sports podcast forever. We love talking about sports and we just grabbed [senior] Will Hanas and went along with it,” Mellon said.](https://mhsnews.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/sam-892x1200.png)